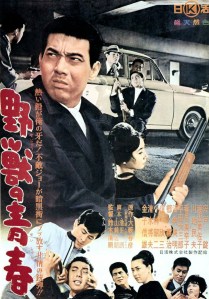

New British boutique film label Radiance has opened strong with Kosaku Yamashita’s Big Time Gambling Boss among its first releases. This 1968 Japanese film is a fascinating contrast and precursor to better known ‘70s yakuza movies from directors like Kinji Fukasaku. More than a historical curio, though, it’s a gripping crime drama in its own right — a study in flaring tempers and perceived slights spiralling out of control.

Do any digging into the history of yakuza on the silver screen and you’ll no doubt stumble across the distinction between “ninkyo eiga” [chivalry films] and “jitsuroku eiga” [actual record films]. Ninkyo eiga dominated through the 1960s, films that framed the yakuza – Japan’s organised crime families – as bound by unbreakable codes of honour and duty. The heroes of ninkyo eiga are constrained by these codes, depicted like modern day samurai, and typically find themselves pitted against less scrupulous villains, battling for the soul of their gang.

By the early 1970s this had begun to change with films like Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series reimagining its yakuza protagonists less as honourable heroes in a dishonourable world and more as violent and capricious villains even when they’re the film’s leads. Because Battles drew on newspaper articles for a ripped from the headlines feel, those films became known as ‘actual record’ films or jitsuroku eiga. Big Time Gambling Boss, released in the late 1960s, therefore feels like one of the last hurrahs of the ninkyo subgenre. It’s a film Radiance pitched as the pinnacle of its era, highlighting its pedigree and the influence it had on director Paul Schrader (writer of the ‘70s Robert Mitchum vehicle The Yakuza), but it winds up feeling like much more than hollow marketing copy: it’s a reputation the film lives up to.

anime

anime  Humanity

Humanity cinema I watch. Sometimes I like to highlight other films when they have some crossover with Japan, Japanese culture, or Japanese actors and directors. The South Korean WW2 drama The Battleship Island (2017), from director Ryoo Seung-wan, is just such a film. Set in 1945 on the

cinema I watch. Sometimes I like to highlight other films when they have some crossover with Japan, Japanese culture, or Japanese actors and directors. The South Korean WW2 drama The Battleship Island (2017), from director Ryoo Seung-wan, is just such a film. Set in 1945 on the  watch. I think it happened when I started massively ramping up the number of films I watch in general. While I might sink tens of hours into a game and would want that time to be well spent, a film is usually over in a couple of hours, and if I didn’t like it, I’d probably be watching another film later that week – perhaps even later that day. And as I’ve written before, even if I walk away from a film disappointed, there’s probably still

watch. I think it happened when I started massively ramping up the number of films I watch in general. While I might sink tens of hours into a game and would want that time to be well spent, a film is usually over in a couple of hours, and if I didn’t like it, I’d probably be watching another film later that week – perhaps even later that day. And as I’ve written before, even if I walk away from a film disappointed, there’s probably still  ‘70s, as well as ‘contemporary’ films from the early 2000s onwards, but with a few exceptions I haven’t seen many films from the 1980s or 1990s. I’ve been meaning to rectify that, in part by digging into the filmographies of Juzo Itami and Takashi Miike. Miike began directing in the early ‘90s and has been incredibly prolific, typically directing multiple films per year for most of his career and only recently starting to dial it back – while still directing at least a couple of films a year.

‘70s, as well as ‘contemporary’ films from the early 2000s onwards, but with a few exceptions I haven’t seen many films from the 1980s or 1990s. I’ve been meaning to rectify that, in part by digging into the filmographies of Juzo Itami and Takashi Miike. Miike began directing in the early ‘90s and has been incredibly prolific, typically directing multiple films per year for most of his career and only recently starting to dial it back – while still directing at least a couple of films a year.  Overlooked at the time,

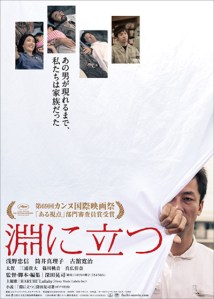

Overlooked at the time,  Some are old favourites I already had in my collection, others are from the growing catalogue of cult and classic films from niche Blu-Ray publishers, and some just happen to pop up on streaming services like Netflix or Sky Cinema. It’s the latter where I’m most likely to see something unusual that I might otherwise have missed – I’m probably going to pick up every Kinji Fukasaku gangster movie I can find, but won’t necessarily see the latest contemporary drama from a director I’ve never encountered. That’s how I ended up watching

Some are old favourites I already had in my collection, others are from the growing catalogue of cult and classic films from niche Blu-Ray publishers, and some just happen to pop up on streaming services like Netflix or Sky Cinema. It’s the latter where I’m most likely to see something unusual that I might otherwise have missed – I’m probably going to pick up every Kinji Fukasaku gangster movie I can find, but won’t necessarily see the latest contemporary drama from a director I’ve never encountered. That’s how I ended up watching  In the West, there was Francis Ford Coppola’s

In the West, there was Francis Ford Coppola’s