I first saw Ghost in the Shell (1995) in the late ‘90s, on a probably-rented VHS, with the American dub (which, to my recollection, actually held up as  one of the better dubs I’ve heard, though I haven’t tested that in years). Since then I’ve revisited it several times, with the original Japanese audio, both before and after I learned to speak the language. I recently had the opportunity to see it in a cinema for the first time, which presents a perfect moment to discuss the film here.

one of the better dubs I’ve heard, though I haven’t tested that in years). Since then I’ve revisited it several times, with the original Japanese audio, both before and after I learned to speak the language. I recently had the opportunity to see it in a cinema for the first time, which presents a perfect moment to discuss the film here.

The following review contains minor spoilers about the identity and goals of the film’s antagonist

Ghost in the Shell is such an incredibly dense film. Visually and narratively, it’s overstuffed with ideas and suggestions and implications. Watching it again, I was struck by how in my memory I had entirely glossed over some of the details, like the preponderance of basset hounds or the subplot with Mares; a foreign military colonel apparently defecting or escaping into the territory in which the film is set, who is accused or suspected of being the Puppet Master. I say “the territory in which the film is set” very carefully, as I’ve never been sure where exactly Ghost in the Shell takes place. Despite the abundance of Japanese characters – Kusanagi, Ishikawa, Aramaki, et al – it clearly takes place in a Chinese-language location. Every sign is in hanzi, without a scrap of hiragana or katakana that might suggest a Japanese setting. It’s worth mentioning that I still haven’t read the original manga, which may or may not shed light on this; unhelpfully, Stand Alone Complex, the anime series also adapted from the same source, is explicitly set in Japan. I’d always assumed the film is set in a deliberately ambiguous Chinese port; the closing shot looking down from Batou’s safe house in the mountains overlooking the vast city calls Hong Kong to mind. Apparently, Hong Kong was indeed used as a visual guide, but the intent is for the actual location to remain undefined.

Huge swathes of the film are devoted to long, slow takes on the scenery, wherever it is. In particular, the sequence set to Kenji Kawai’s “Ghost City” is one of my enduring images of the film, a kind of interlude or intermission between the two halves of the story. Long, lingering shots of the buildings, the ferries, the waterways, the neon and the decay. The level of grime and piles of trash are straight out of William Gibson’s earlier work or Philip K. Dick’s kipple. Though visually striking, it might be easy to dismiss as filler, yet the sequence is richly animated; it’s no placeholder to bulk out the run time with cheap, still scenery.

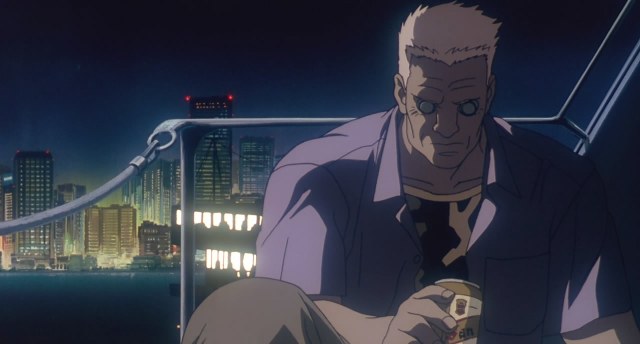

I’m sure that Ghost in the Shell (along with the videogame Deus Ex, from 2000) is responsible for my fascination with cyberpunk, artificial intelligence, and prosthetics. The film posits a 2029 where ‘full body cyberization’ is possible, the human brain encased in a shell that can then be inserted into a cyborg body. Throughout the film it is ambiguous who is fully human and who is a cyborg; Kusanagi is a full-cyborg, with only a human brain remaining. Batou, her partner, is similarly heavily cyberized. Togusa is singled out for being ‘almost human’, he has only a jack to connect to networked computers; the film makes explicit mention that he is picked to join a team of cyborgs for this exact reason. In a recurring theme, Kusanagi tells him that any organism or organisation that is too specialised risks extinction.

It’s actually an oddly narrow view of the future, one in which cyberization and robotics are perhaps the only notably futuristic elements. Like many older science fiction stories, it fully embraces the internet and the networking of computers, devices, and cyberized people, but it fails to predict or utilise wireless technology at all; the Major physically plugs into Division 9’s armoured van to access the network and drive by wire, and the end of the film essentially requires that physical access to a cyborg body is necessary in order to interface with it (years later, Stand Alone Complex would allow for the advent of wireless technology, letting cyborgs wirelessly connect to networks at the cost of being vulnerable to remote hacking). The focus on cyborgs and robotics gives the story’s central questions room to breathe: what does it mean to be human? Is artificial life really life?

There’s so much philosophizing in Ghost in the Shell it’s probably easy to get lost in different potential readings. Much of the latter half of the film is concerned with evolution – in an unsubtle nod, the spider tank’s spray of bullets shred a huge mural of a tree whose branches end in “hominis”. The Puppet Master, an artificial intelligence built for cyberwarfare, essentially seeks to procreate and evolve.

Yet for me, the more interesting questions revolve around the nature of consciousness and what constitutes a human being in a world full of cyborgs and humanoid robots. Cyborgs like the Major are like the Ship of Theseus, their organic body parts gradually replaced with artificial components until, potentially, nothing of the original remains. In what is probably my favourite scene, Batou and Kusanagi argue over this, questioning whether a cyborg can truly know if they were once a human being, or one whose organic parts had died and been replaced entirely with mechanical ones, or whether there had ever been an original, organic human at all. Kusanagi notes that a cyborg can never see their own brain, which is supposedly encased in a shell. The last vestige of what made them human is sealed from view. They rely on technicians who maintain their cyborg bodies, but as Batou discusses with Aramaki, there’s only so far down the rabbit hole you can go, questioning how reliable those technicians are.

I could go on, but there is more to the film beyond the musings on technology and psychology (which seems like a slightly counter-intuitive comment, when usually one has to argue there’s more to a film than its visuals or action). The animation has aged well, though again, I was amazed by how much more dated it looked than I remembered – not bad, but just very clearly from a different era. The way people are drawn is very different to the current lean towards taller, more slender characters – people seem squatter and blockier. Togusa’s high-waisted slacks and dashing mullet particularly amused me. The design of the Major is interesting. The film spends an inordinate amount of time focused on her breasts, but she’s also drawn very masculinely and well-muscled. This is in contrast to the way she speaks, using feminine language like あたし (atashi, a female variant of ‘I’) and わ (wa, a female sentence ending marker). I think her frequent nakedness is meant to represent her disconnect from her body and from social norms – just look at the way Batou is usually the one to cover her up with his jacket. She doesn’t sexualise her nakedness, but his actions do.

The action is contained within a few short sequences, and can be characterised in contrast to the moments of stillness surrounding it. When Batou and the Major are hunting one of the Puppet Master’s hackers there’s a startling difference between the over-the-top gunfire and explosions and the quiet during the pursuit (with the extremely memorable shot of the massive plane moving slowly overhead in the patch of sky not covered by skyscrapers). At the end of the film, the battle with the spider tank is again silence punctuated with gunfire and the sound of footsteps in water.

I really could not recommend Ghost in the Shell enough. After two decades it remains one of my favourite anime and my favourite films, full stop. It’s almost impossible to gauge the influence it has had on other films and science fiction storytellers, and on me personally, and how I perceive transhumanist technology.

Of course, it’s also difficult to discuss the film in 2017 without mentioning the coming remake, which as I write this is still a couple of months away. I’m not someone who feels that nothing can or should ever be remade; some of my favourite works are remakes or reimaginings, from The Thing (1982) to The Departed (2006) to Yurusarezarumono (Unforgiven, 2013). I think in particular when the films in question are both adapting a piece of original source material, there’s room for interpretation – just look at the differences between Ghost in the Shell and its sequel Innocence, the Stand Alone Complex series, and the recent ARISE version of the setting. Rupert Sanders’ version looks like it draws very heavily on the visuals of Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (with a Blade Runner-esque emphasis on giant advertisements), but the story presented in the trailers seems more akin to RoboCop than the cyborg world shown in Ghost in the Shell. My worry is not that the new film be whitewashed, but that it will lose the philosophical nuance that makes this one great. That film’s success or failure, however, will not diminish the brilliance of the original.

Ghost in the Shell / 攻殻機動隊 GHOST IN THE SHELL (Kōkaku Kidōtai Gōsuto In Za Sheru)

Director: Mamoru Oshii

Japanese Release Date: 18th November 1995

Version Watched: 82 min [Shown in Cinemas by Manga Entertainment, possibly based on the 2014 HD film print given the poor subtitles]

I recently had a rewatching experience of GitS similar to yours, although it was with a friend who wasn’t so into it (I forgot just how heady and obtuse it was). I’m actually surprised to see you say the dub is great because of this, not that I’ve watched it myself but it seems like a difficult movie to translate for a Western audience as dubs usually go further in localization that subs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well like I said, it’s been a very long time since I’ve seen it with the dub, so it is possible it hasn’t aged as well as I’d hope! I might have to check out the English language audio at some point to see how it holds up. I think – and I’m speculating a bit here – that because the film deals more with abstract science/technology etc. and less with Japanese cultural concepts, the dub (and the localisation in general) doesn’t suffer as much. There’s less temptation to alter things for a Western audience because they’re not quite so specific to the original Japanese language script.

It’s funny you should mention seeing it with someone who wasn’t into it, though – I was sitting in the cinema thinking “I hope everyone here has already seen it”, because I think you’re right, it is definitely heady and obtuse. If it’s not what someone was expecting I think it might be quite difficult to grasp and to enjoy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the real problem for him was that it starts off with a bunch of action before shifting to philosophizing in Act 2B/3. I think the film’s length is to its benefit though, it doesn’t outstay its welcome. It’s also a film that greatly benefits from rewatching as I can’t imagine being able to keep up with it on a first viewing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m relatively new to anime and am going to watch this one soon – the hype around the Hollywood release has pushed me to it. Thanks for your post – I’m looking forward to checking out this much-loved film and I suspect I’m going to love it. I love reading other people’s detailed takes on films.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading! For a long time I wasn’t much of an anime fan either and this was one of the few films I’d seen. As you can probably tell from the review it remains one of my favourites, so I hope you enjoy it when you check it out!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know I’ve watched some Ghost in the Shell as a kid. But for the life of me, I can’t remember much about it. Perhaps that’s because I was still literally a toddler when it came out. Although I do remember watching some eps of it when I was a little older…still a kid, though. Will probably watch it properly now as an adult, especially since it returned to the forefront with its controversial live-action film recently.

LikeLike

I think the series (Stand Alone Complex) is a lot more accessible than the film. I’d be hard-pressed to choose one over the other for which I like more, but so far at least, there hasn’t really been a version of Ghost in the Shell that I’ve disliked – with the caveat that I haven’t seen the live action attempt yet.

LikeLiked by 1 person